I got to Will Knight’s MIT Technology Review article about the difficulties of understanding decisions made by artificial intelligence via a link to Monica Anderson’s sour comments to it, which slams the “reductionists at MIT”.

“When a human solves a problem, it would be preposterous to demand to know which neurons they activated in the process”, she exclaims. “Artificial intelligences will operate more like humans than like other machines. […] We need to treat [them] more like humans when it comes to issues of competence, reliability, and explainability. Read their resumes, ask for references, and test them for longer periods of time in many different situations.”

The article is interesting, and so are Anderson’s comments. I am thoroughly unsure what to think about this myself, but I’ll add a few tentative reflections:

I don’t have an issue with computer systems helping us out with things we can’t do ourselves, without explaining exactly how to do it. Letting an artificial neural network sniff out the onset of schizophrenia is like letting a dog sniff out a missing person in the woods. It has a skill we don’t, so we use its services, without worrying about exactly how it does what it does.

But letting computers make, or advise, decisions that humans would otherwise make is a more delicate issue. When we do that, we project our expectations from human decision-making on decision-makers with a completely different disposition. That’s especially problematic if we can’t extract its arguments, because if we could, we might find that they are preposterous and immoral. Knight mentions research that has found AI image recognition systems susceptible to certain equivalents of optical illusion that exploit low-level patterns the system searches for. There may be similar illusions in the case data of legal decisions.

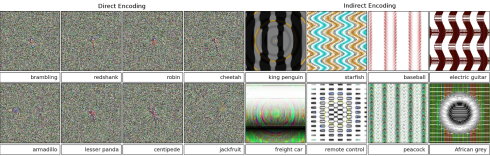

Figure from Deep neural networks are easily fooled: High confidence predictions for unrecognizible images by A. Nguyen, J. Yosinsky, and J. Clune

(On a tangent, humans are susceptible to analogous illusions, targeted at how our brains interpret information. Art is based on them. A creature that recognized objects in a completely different way might be mystified as to how we can interpret a simple line drawing as, say, a cat, or a smiling face.)

It’s important to realize that even if a computer’s judgements are correct in a statistical sense, we may not find them acceptable. Say, for instance, that it is possible to improve predictions for human behavior or preferences based on a person’s sex or skin color, and that the prediction is useful in deciding how how to treat that person. Then using data about people’s sex and skin color could make a system more efficient. More people may could be satisfied with how they are treated. But what about the treatment of the others, those that are less satisfied? We have names for that: discrimination, prejudice.

We want to avoid that for moral reasons, at almost any price in overall performance. And in order to do so in constructing decision systems, we need to have a clue to how the decisions are made.